Consumer personas are like horoscopes. “Nicole is careful with her spending, but under right circumstances is willing to splurge on herself if the mood strikes her.” Read carefully, and psychographic profiling is full of generic, unverifiable, ambiguous, and often contradictory language that supports a number of interpretations.

Psychographics also mask the inherent unpredictability of our tastes and the complex ways they interact. My sister-in-law lives in an affluent suburb of Chicago. She owns a piece of Away luggage (before its fall from grace) and gets newsletters from Everlane. On the surface, she is a HENRY, but in reality, she is a middle-aged married mother of three who now has both brands because they relentlessly pursued her through direct mail discounts until she finally gave in.

Inferring about psychographics based on the products people buy is unreliable. People buy the same things for wildly different reasons: there’s a discount, they are in different moods at different times, other people have them.

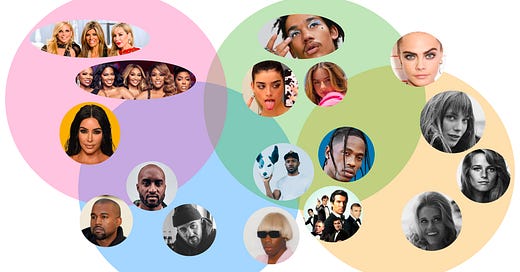

Equally problematic is personas’ focus on the individual because it ignores the fact that people are social creatures. They belong to communities and are part of influence networks that they use to decide what to watch, read, buy, and pay attention to.

Thanks to the Internet and its numerous influence networks, products across categories are now more susceptible to trends than to individual preferences. A show becomes popular because a lot of people watch it, and it’s entirely possible that a big chunk of the show’s audience does it not because it reflects their interests or values, but because everyone else they know is watching a show and they do not want to be left out (Netflix even unrolled the fast-forward viewing option for those).

Instead of focusing on individuals, we should focus on their relationships and look at the communities they belong to.

Netflix’s taste communities are a variation of this idea. This streaming platform’s 125 million global viewers are divided into 2,000 “taste clusters” that group people based on their movie and TV show preferences. At the same time, Netflix content is extensively tagged and based on these tags and their connections, divided into microgenres. Micro-communities and micro-genres are then matched up.

Thanks to its banks of data, Netflix goes beyond the psychographics of its average customer. They know the relationship (“matchmaking”) between its members and its content; and also useful things like how many hours of watched content per month makes its subscribers unlikely to cancel.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Sociology of Business to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.