The Decade of Two Luxuries

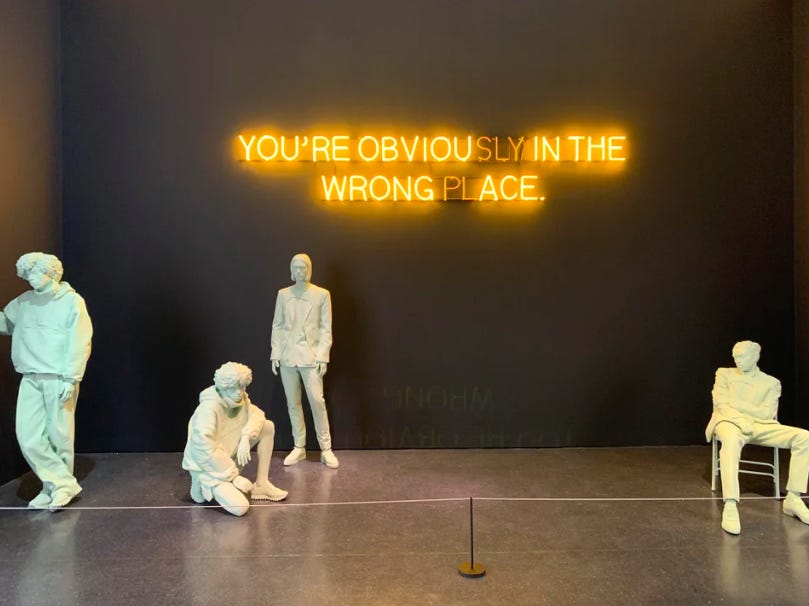

A few years ago, Off-White’s 2016 Fall-Winter runway show featured “You are obviously in the wrong place” neon sign referencing a line from the movie “Pretty Woman.”

It’s a good metaphor for luxury since 2010. There wasn’t a decade where luxury meant more, and less. The use of the term expanded to include brands from Nike to Sonos to Shinola to Supreme to Kim Jones’ Dior collabs. It also constricted to ephemerals like time, space, privacy, self-actualization. The Louvre Abu Dhabi’s “10,000 Years of Luxury” exhibition ends with an hourglass.

This is a moment of the great luxury bifurcation.

On one end, there’s Big Luxury. Big Luxury is commercial, and its goal is to push consumers to buy more. Big Luxury is the domain of streetwear collaborations and “premium mediocre,” which emphasize merch and logos that turn everyone willing to spend $600 on a t-shirt, a branded hat, or a belt into a luxury consumer. In the Big Luxury, a high-end piece of jewelry is selected to go with the latest sneakers or a handbag. A taped banana is art. A hoodie is the status symbol. Access is a commodity: because goods from luxury houses are ubiquitous, the only way to provide differentiation is via faux limited edition and drops. It’s a marketing strategy that masters distinction without a difference, where everyone owns a variation of the same thing under one brand umbrella. As sociologist Georg Simmel observed a long time ago, fashion raises “even the unimportant individual by making them the representative of a class, the embodiment of a joint spirit.” So does Dior x Stussy. In the Big Luxury, democratization is good, and elitism is bad, a sentiment perfectly captured by Abloh: “I am trying to communicate with tourists and purists at the same time.” Big Luxury is a global moneymaking machine, fueled by new markets, new consumers, new wealth, growing conglomeration, and hype-driven social media.

On the other end are those who seek and identify with the “exceptional artisanal work.” We are not luxury, says Hermès. We are high quality. As of yet unnamed, this domain of aspiration champions displays of human creativity; algorithm-free, analog taste; and admiration for well-made things. We find these pillars among the family-oriented, cottage industry of the likes of Hermès, Loro Piana, The Row, Noma, Hong Kong’s Upper House, and in the vintage market. Financial Times’ How To Spend It, also known as “the shopping list for the 1%,” has recently started to introduce us “Makers” at regular intervals, a signal where the money and the attention of the wealthy is going.

Choose one of the paid subscription options to access the rest of this analysis.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Sociology of Business to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.