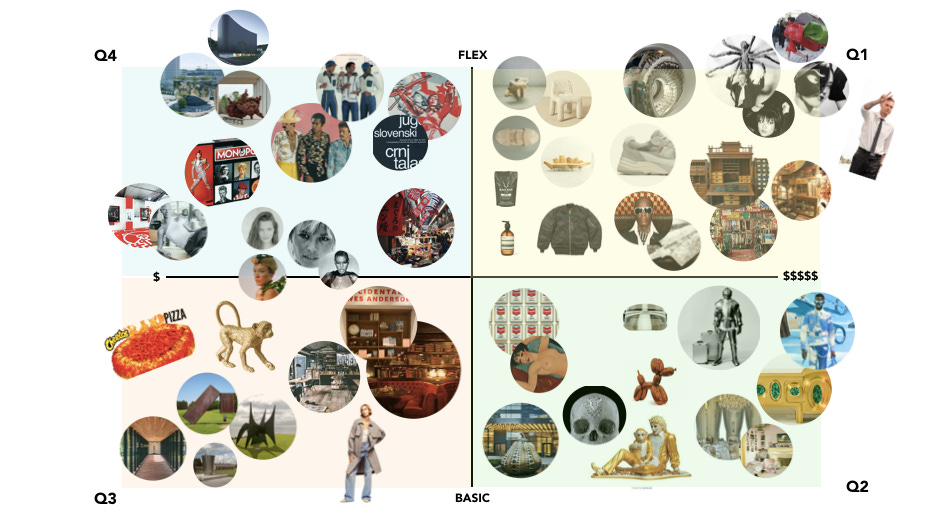

The taste map

How consumers' taste shapes brand strategy

Welcome back to the Sociology of Business! If you are not subscribed, join the community by subscribing below. To kick the new year off, here’s also the 30% off promo code SS330 on my book The Business of Aspiration, applicable on the publisher’s website. Let’s go.

Taste shapes how we see the world. It encodes symbols and meaning into products, places and people. Taste connects the symbolic and the commercial, and links aesthetics to consumer behavior. It reveals consumers values, identity and their desired status. If a person likes Stella McCartney, they signal their commitment to sustainability, trendiness, quality and also their ability to afford expensive clothes. By conveying various dimensions of consumers’ life, taste creates new inequalities.

Brands are in the business of taste.

Knowing how consumers are distributed on the taste map informs brands’ allocation of their production, distribution and marketing resources, informs their communication and defines their messaging.

The new taste map

Good versus bad taste, art versus kitsch, professional versus amateur disappeared at the moment when Balenciaga put Crocs on the runway - and arguably much earlier. The timeline of rendering the dichotomy of highbrow and lowbrow irrelevant can be traced to Elsa Schiaparelli and her Surrealist friends through Andy Warhol to Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons.

Taste and social and economic class went hand in hand. A person needed exposure to good taste in order to know what good taste was. Social milieu and education train personal sensibility in reading taste signals, which remain invisible to those without this taste dictionary and vocabulary. Taste a system of signs: a Telfar bag is meaningful and coveted only to those who can decode the culture that Telfar trades in.

Through its semiotic dimension, taste reproduces a person’s social and cultural capital and creates social distinction. At the time of traditional taste oppositions, it was easy to classify status, money, class and prestige and place a person within the social fabric. As Bourdieu noted, “one’s capacity to see (voir) is a function of the knowledge (savoir).” But, like Cheetos Pizza, it’s hard to tell these days what tastes bad but is status-signaling, coveted and popular. Big Luxury customers are full of money but scant on opinions: they buy LV not because they like it but because it’s LV.

Taste is still used to create social distance: between the creative class and others, between modern aspirants and the Big Luxury consumer, between plugged-ins and basics. It is a powerful mechanism of signaling identity and belonging, and it is increasingly niche.

The four quadrants of taste

In place of the old taste dichotomies, there’s the new taste map. It is structured around two axes.

The vertical axis captures taste flex. It is a continuum of cultural savvy: the ability to perceive the culture ironically, to have a degree of creative remove, to take things, people and ideas out of their context, to know the history and have enough confidence to play with it. The opposite of flex is being basic in a sense of earnestly following trends and not having an opinion about well, anything. It’s a domain of mimetic desire and imitation, and it captures women with shoulder pad The Frankie Shop t-shirts, bike shorts and a stack of Cartier bracelets who adhere to traditional taste codes and rituals.

The horizontal axis is price. It emphasizes the non-linear relationship between modern taste and its cost. Majority of expensive things - art, vacations, luxury fashion - means today mostly that someone has enough money to afford them. This is the domain of Warhols, Koons, Mariah Carey home design sensibility and Big Luxury. It is inaccessible to those who cannot afford it, but also unappealing to a lot of those who can. The latter group considers this domain insufficiently differentiating when it comes to their desired social standing.

The top two quadrants (Q1 and Q4) are about status signaling through showing off one’s cultural savvy and plugged in-ness. This is the territory of the modern aspirational economy, and has less to do with money and more with having knowledge, aesthetic sensibility and the right creative network. Examples are: Telfar, downtown art galleries, food and drink connoisseurship, road trips, small wooden stools.

The bottom two quadrants are the domain of traditional economy, where price is the key determinant of access and signal of status. This territory spans from Zara to Prada, and is often directed by the same aesthetic. Dynamics in this taste market is a cycle of imitation and distinction. Trends are created in Q2, then imitated and scaled in Q3. This imitation of products, people, places and ideas that diminishes their exclusivity and value. Examples are accessibility of once unique places like art institutions in rural areas (Storm King, Louisiana Museum), speakeasy and coffee shop aesthetics, luxury fashion trends.