How luxury lost its soft power

Luxury doesn’t need a new competitive strategy. It needs a new cultural strategy.

Welcome to the Sociology of Business. In my last analysis, What is next for collaborations?, I looked into brands’ growth through crafting full-stack experiences. For sponsorship options, send me an email. If you are on the Substack, join the chat and I’m happy to respond to any questions in the chat or comments here.

The Sociology of Business is now offering 25% GROUP SUBSCRIPTIONS, make sure to take advantage of it. Pre-order my new book Hitmakers: How Brands Influence Culture, and find me on Instagram, Twitter, and Threads. With one of the paid subscription options, join Paid Membership Chat, and with the free subscription, join The General Chat on The Sociology of Business WhatsApp group.

There is no shortage of luxury analyses. Most of them focus on geo-politics, macro-economics, market growth strategies. The industry’s slowdown is viewed in the economic context.

The problem is cultural. Luxury lost its soft power.

Luxury’s soft power kept its value and price together. Price made something more desirable (the Veblen effect) and no one questioned the price thanks to perception of value. This value was material, but mostly cultural and social: when an item sold too well or too quickly, a luxury brand would discontinue it.

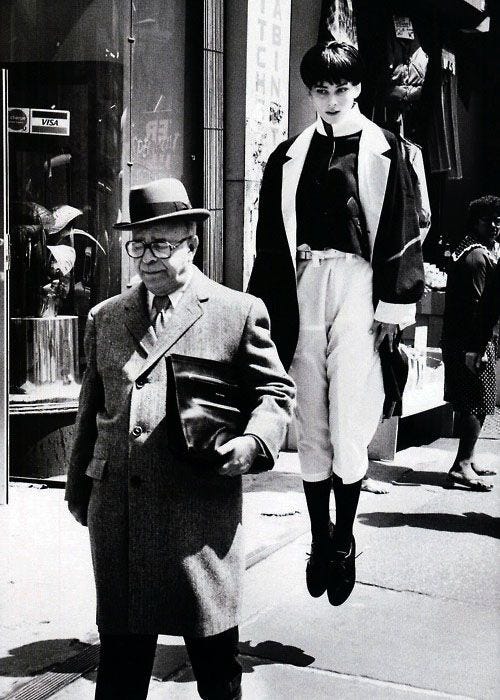

The late Alber Elbaz said, “we are no longer the industry of newness, because that was taken by technology, but we are still an industry of a man and a woman, of a thread and a needle, and of fabric, and a dream.” Once, luxury was by default innovative, creative and provocative. Arbiters of taste, like Schiaparelli, Chanel, Balenciaga, Saint Laurent or Dior created looks that lasted. They changed how people dressed.

Luxury’s desirability - perception of value it enjoyed - fueled its economic growth. There are few industries more powered by dreams, imagination, fables and heritage than luxury. Luxury growth didn’t came from products, but from the intangible social and cultural capital it created. Cultural hits - Hermès Birkin, Chanel tweed, Rolex Daytona - became market hits.

It is this intangible social and cultural capital (or its lack) that made Virginie Viard step down from her creative director role at Chanel, at the same moment when Chanel’s financial results climbed by 14.6% to $19.7 billion. Viard’s work was a commercial but not a critical success. Cathy Horyn noted at the time, “Money isn’t everything. With a house of Chanel’s status, its extraordinary story, the executives and owners ought to be equally - and maybe more - concerned with creativity and newness.” A prominent cultural commentator told me, “Chanel had to save face with regards to criticism. They are still old school, with values other than money. Chanel wants both critical and commercial praise.”

Brunello Cucinelli is known for citing Horace, Cicero, Socrates and Aristotle and meditating on the idea of humanistic capitalism. The Dream of Solomeo is a celebration of a lifestyle, humanity and betterment. Cucinelli's luxury beliefs are as expensive as his clothes.

In Christopher Green’s Ven.Space, a menswear boutique in Brooklyn, hangers hide brand labels. The idea is for customers to “feel the fabric first, then look at the garment, then go to brand, and only then to price,” Green noted in recent Eugene Rabkin’s piece for the Financial Times.

Luxury exists in the social and cultural exchange system, not in a market segment. It is glib to think that a different market growth strategy will save luxury. To save itself, luxury needs to regain its cultural power.

Cynic is a man “who knows the price of everything, and the value of nothing,” noted Oscar Wilde. He might have as well been describing today’s luxury market.

Seemingly overnight, luxury products’ price unbundled from their perception of value - their desirability - and turned them into commodities.

But the shift in consumer behavior happened earlier. Having something expensive stopped being necessarily desirable. As I described in my first book, The Business of Aspiration, desirability became linked to taste, access, belonging, knowledge, story, personal betterment. Most coveted became low-tech displays of human originality and creativity - limited edition items, unknown yet discerning brands, work of human hands, uniqueness, exclusivity, good food and wholesome life. “Craft is our technology,” noted Matthew Blazy when he became Bottega Veneta’s creative director.

When the capital is different, so is the trade.

Growth motor is not price. It’s taste, aesthetics, curation, belonging and storytelling. A Renaissance bent that can mix references from art, design, music, architecture, fashion, travel, film, photography, gastronomy, philosophy.

Where, exactly, is the value?

Luxury is a game of identity. Identity is what differentiates luxury strategy from strategy of premium and mass brands. Identity commands value perception, and prevents cost-per-wear and price-value calculus. It also makes a brand incomparable: premium and mass brands communicate how they are better/cheaper/faster than competition. Luxury brands don’t. (Or, at least, those luxury brands that retained their incomparability do not: Hermès sales are up 11.3 percent in the Q3 of 2024. Bottega Veneta and Brunello Cucinelli have also grown, as did Prada.)

The list is short. Luxury brands literally lost the plot.

Instead of doubling-down on identity, most luxury brands doubled-down on creating more products.

Without identity, a product is commodity.

Without identity, a brand is a glorified production facility.

A lot of luxury brands organized themselves as commercial entities fiercely focused on their own efficiency, cost-cutting and bottom line. This growth strategy made a lot of them forget who they are, what they stand for, and the role they play in culture.

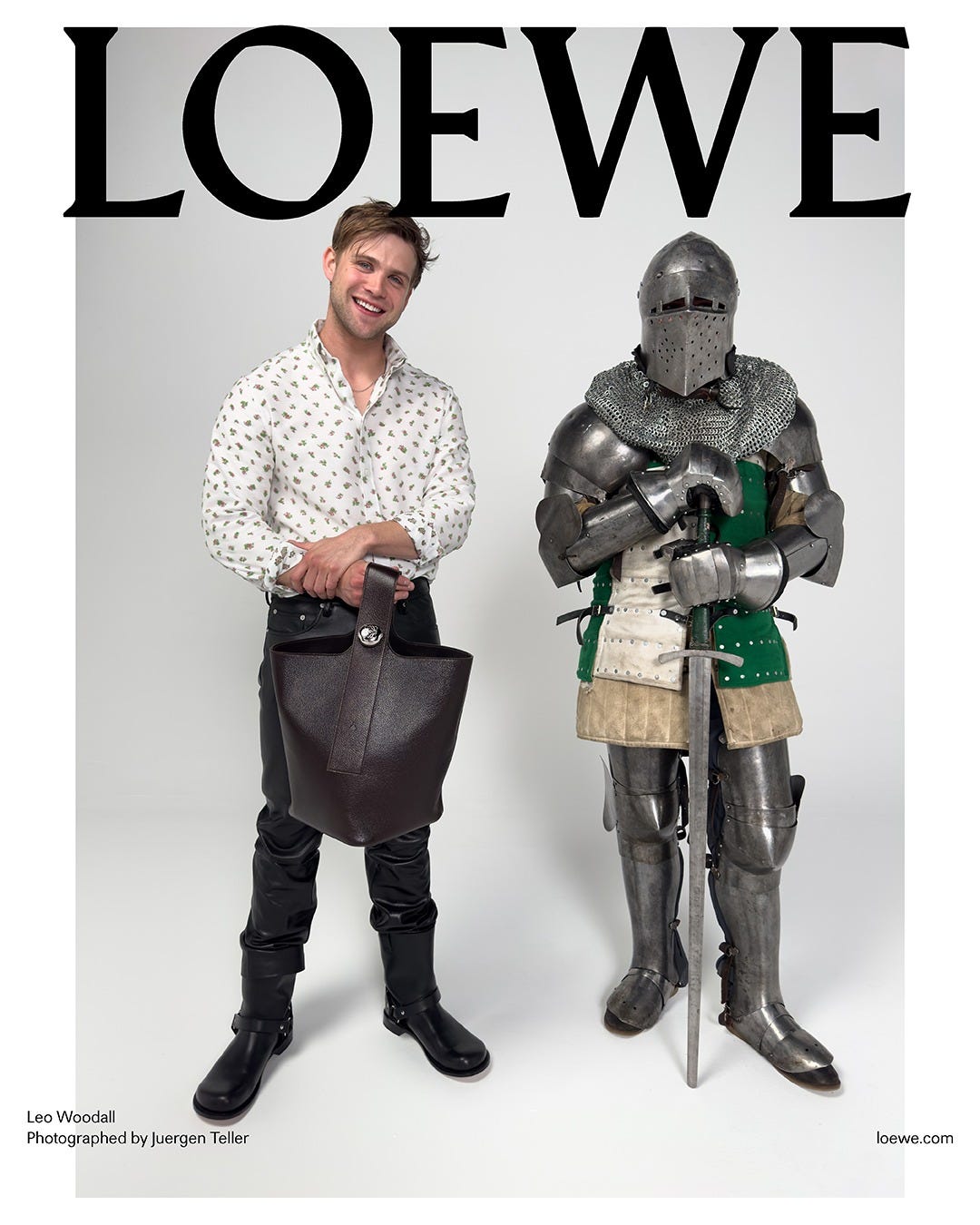

Luxury’s identity crisis isn’t new. More a decade ago, there was a great luxury bifurcation, where luxury never meant more and less. On one end, Big Luxury was formed: the domain of fast growth, new markets, new consumers, new wealth, a constant change of creative directors, a constant newness and brand reinvention, hype-driven social media, and premium mediocre. The personal luxury market grew 30% from 2019 through 2023. It is a reflection of the late industrial age MO, where scaling growth is linked to incessant production. Automotive, publishing and hospitality have all tried this, before being forced to radically rethink their approach to growth (and survival). Big Luxury reached ubiquity, both in terms of products and celebrities and influencers it uses in its marketing. With Big Luxury, marketing is all there is. Creative directors are in charge of coming up not with the ways people dress, but with campaigns that will grab more attention and sell more products. It’s hard to be a taste arbiter when there are shareholders to respond to. Big Luxury marketing masters distinction without a difference (or identity). As sociologist Georg Simmel observed, fashion elevates “even the unimportant individual by making them the representative of a class, the embodiment of a joint spirit.” So does a Balenciaga coat.

On the other end, there are brands smaller in scale and market penetration, like Bottega, Hermès, Prada, Cucinelli. Family owned, they identify with a set of beliefs, ideas, a long term vision, and exceptional artisanal work. This domain of luxury champions displays of human ingenuity, algorithm-free, analog taste, and admiration for well-made things. It is more sensitive to what consumers are willing to spent time and money on - taste, aesthetics, ethics, identity - than its Big Luxury counterpart. It also seems to seek to re-establish the link between us and our culture, society, art, environment, humanity and betterment. In this domain, desirability is powered by identity. Here, brands know that who they are and the ideas they bring to the world are the most powerful thing about them. Despite or, more likely, because its obsession with identity, this sector is currently growing more, and experiencing economic slowdown less, than Big Luxury.

Perhaps they are better at predicting the future. Science fiction writer Frederik Pohl said that a good science fiction story should be able to predict not the automobile but the traffic jam. To predict the “traffic jam,” luxury doesn’t need a new competitive strategy. It needs a new cultural strategy.

Big luxury is a big experiment. We've never had huge publicly traded conglomerates driving such a large portion of the luxury market before. Could it be the paradigm has reached it's full potential and is now on the decline? I for one hope so. I think this system does not serve the customers, creativity or quality, though I fear it's too big to fail.

Forgot to add, empires fall when they lose touch with people let alone fashion houses.